More and more people are becoming interested in shamanism, especially the Amazonian tradition, involving the use of visionary plants such as Ayahuasca. Indeed, this medicine has seen an incredible boom in recent years. Ayahuasca-related tourism has developed at a pace that seems almost out of control, and retreat centers are sprouting up like mushrooms in South America. In the Iquitos region alone, in the Amazon basin, there may currently be up to 70 centers offering this kind of service.

More and more people are becoming interested in shamanism, especially the Amazonian tradition, involving the use of visionary plants such as Ayahuasca. Indeed, this medicine has seen an incredible boom in recent years. Ayahuasca-related tourism has developed at a pace that seems almost out of control, and retreat centers are sprouting up like mushrooms in South America. In the Iquitos region alone, in the Amazon basin, there may currently be up to 70 centers offering this kind of service.

This popularity does not seem to be limited to the South American continent alone, as this medicine is now available all over the world, including in many countries where its use is still considered illegal. Especially in trendy circles, where having an Ayahuasca ceremony now seems to be a must: for example, we can see more and more references to Ayahuasca in Hollywood productions and US series. In 2016, an article in the New Yorker estimated that around a hundred ceremonies were performed every night in Manhattan alone.

This means that more and more people now have an opinion on the matter, regardless of the nature of their experience, the context, or the people with whom they did it. Yet the subject is complex, very complex indeed. First of all because it involves all the subtleties of a medicine we do not understand very well, and which holds many mysteries. But also because it brings out all the themes related to being human, in the broadest sense.

When browsing Internet discussion groups, social networks, or some specialized blogs, one question comes up regularly in conversations: what is a “good” or “real” shaman? After all, this is a legitimate question. For those who want to experience this medicine, it is normal to look for a reliable practitioner. Especially since its effects are powerful, people want to limit the risks and stay safe. And yet, the answer to this question is far from being simple.

The apprentice’s path

Perhaps it would be good to recall what a shaman is in the Amazonian tradition (or rather “curandero,” healer in Spanish). Note: I am going to use the masculine gender here for practical purposes, but it is obvious that there are also wonderful medicine women that are extremely appreciated and respected.

It is therefore generally a man or a woman from a tribe native to the Amazon basin. The curandero‘s encounter with plant medicine often occurs very early, either because he comes from a lineage of shamans or because the plants “called” him in some way. It is a long and very demanding apprenticeship. The main method of learning is called “la dieta” (the diet). It consists of spending long periods of time in isolation in the jungle, following a very strict diet and keeping interactions with others to a minimum. This ascetic retreat is accompanied by the taking of many plants, carefully catalogued over the centuries. The diet, because of its introspective and meditative nature, promotes connection with these master plants. The apprentice then enters into communion with the spirits of these plants, who will become his allies and teach him their medicine – notably through songs, the icaros, which will then be sung during the ceremonies to invoke the power of the plants and heal the participants.

Needless to say, this is a path that requires total commitment, and one that can seem daunting for current generations, even among indigenous tribes.

The Amazonian shamanic culture

In our western culture, we have a very romantic image of the shaman. He is a wise man living in the jungle, in communion with nature, speaking with the spirits and being able to guide us towards a reconnection with our deep human nature. That’s partly true, of course. But it’s a little more complicated than that. First of all, we are dealing with men and women, with their own personalities, flaws and wounds – not saints or gurus who have necessarily attained enlightenment. Moreover, we are talking about a fundamentally different culture. As Jacques Mabit, founder of the Takiwasi center, explains very well, shamanism in the Amazon is used for very diverse and pragmatic purposes. Life in the jungle is not free from danger, far from it, and this practice was always used above all to protect the tribe: to heal, of course, but also to prevent danger through vision quests, and to anticipate potential attacks from enemy tribes. Even resorting to witchcraft, to protect oneself or attack the opponent. For some, shamanism is a weapon, both defensive and offensive. The use of witchcraft (“brujeria“) is still widespread today in the Amazon. It can be a survivalist, and ultimately, warrior approach. Not necessarily a quest for understanding, purpose and personal development, as it is considered in our western world. This tradition, because of its great richness, can therefore cover all these fields, and be used in many ways.

Some people state in an authoritative way that a true shaman must necessarily be a native, belonging to a clearly identified tribe (Shipibo, for example), descend from a powerful lineage of curanderos, have a very long experience in the field, and practice the tradition to the letter. It is not uncommon to see a form of snobbery or even condescension on the part of some who, conveniently, are precisely the students of a master who corresponds to these criteria. In other words, “my way is the right way, all the others are impostures.” Fundamentalism is never far away…

The choice of the heart

Yet these criteria are quite simplistic, and do not say much about the practitioner himself. It should be noted that this reasoning is ultimately very Western, and based on our obsession with diplomas and prestigious schools. One day I was in an Ayahuasca ceremony, during which I was examining my own impostor syndrome as an apprentice curandero. It’s true, after all: even though I’ve worked hard on myself to avoid the pitfalls of my ego, even though I’ve done diets, even though I’ve approached this path with the greatest respect and all the humility I could find, I don’t have the references that some people seem to consider indispensable – no renowned master to put on my business card, no prestigious lineage…

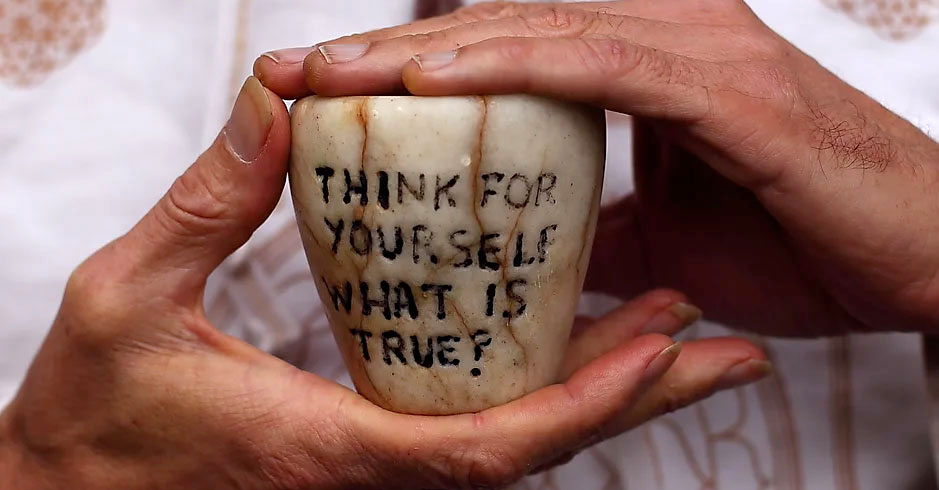

As I pondered all these considerations, the plant told me the following:

We tend to think that someone who went to Harvard is bound to be very competent. And someone who went to public school will be mediocre. This is already a simplistic preconception, but applied to a practice that relies so much on human qualities, this reasoning becomes preposterous. Of course, there are wonderful healers in the Amazon, true masters in their art, who inspire admiration. No one questions this. But more and more cases of abuse, especially sexual abuse, are also surfacing today, even though they concern very reputable shamans who met all the criteria of legitimacy and respectability.

Anyway, who said the Amazonian shamans have all healed their own “shadow part”? Besides, why would they do it? They have probably never heard of this concept, or of Jungian psychology, for example. We project a lot of fantasies on a culture that is not our own.

You are the healer

So yes, of course, it is crucial for a shaman to have experience, because journeying in altered states of consciousness and supporting those who participate in ceremonies is a very delicate task. But we must not forget that the shaman is a guide: the real healing work is done between you and the plants. I would even say between you and yourself, the plants being a powerful vector of introspection and self-discovery. It is therefore important to be able to call upon a curandero who will be able to support you in this experience, during the ceremony, but also afterwards, during the integration of the teachings you will have received. Will this shaman have the ability to understand your suffering, to have compassion and empathy for you, to resonate with the challenges you face, and to give you enlightened advice? And if these points are so important, is it impossible to accept that this tradition – which I deeply respect – evolves today to serve a greater cultural diversity?

It is now increasingly difficult to generalize. As said above, there are fabulous indigenous shamans, but also scammers attracted by the dollars of gringos that flood into the Amazon. And there are also some very good curanderos of western origin, who do not necessarily have the same labels, but who offer another quite remarkable form of therapy. And then there are also irresponsible people who play shamans after having drunk Ayahuasca three times in their life. Everything exists. The key word here is “discernment.”

It would be very arrogant of me to judge who is good or bad at their practice. But, in addition to experience, I think it is important to look for the following qualities in any practitioner, whether famous or modest: humility, responsibility, compassion, empathy and integrity. It is not always easy to determine whether someone has these qualities, but to me they will be much more valuable assets than a prestigious pedigree.

Some basic clues

To conclude, I would like to list some things I have observed during my apprenticeship and practice, and that should perhaps raise some red flags if you encounter shamans with the following behavior:

– He immediately presents himself by boasting that he belongs to a lineage of powerful healers. First, this is often not true, but no one will go and check it out. Secondly, it is a simple way to gain immediate legitimacy, even if the lineage has never made the curandero. Somehow the shaman hides behind his heritage, and is no longer accountable as an individual. A truly experienced shaman won’t even need to promote himself with this argument.

– He claims to have supernatural powers. He thus puts himself in a central position: he is the one who will “do the job,” who will heal you with his power. But a shaman is an intermediary, he is at the service of the medicine. A good shaman therefore recognizes that the true healers are above all the spirits and the plants… and particularly yourself!

– He uses an obscure fear-based language: you have been the victim of a bad spell, you have dark entities clinging to you. Of course, only he knows the right icaros and the right rituals to get rid of them. He thus tries to create a relationship of power and dependence.

– He tries to seduce you (especially for you ladies): you are special, he received a message just for you during the ceremony and you have to work individually together. He can even tell you that his sexual energy is very powerful, and that he can heal you with it. No comment…

– He makes you promises in regards to a miraculous healing. This is still something we see too often, and it is totally irresponsible. If you encounter this case, I advise you to run away, or at least to take a step back.

The leap of faith

Finally, I would like to conclude with a very personal reflection. It is normal to want to learn about a shaman, and try to sort out the “good” and the “bad.” But this binary approach is rarely in accordance with the complexity of life. We are all mirrors for each other, and we always have something to learn from others. As the saying goes, “when the student is ready, the teacher arrives,” even though the teacher may not necessarily look the way he or she is “supposed to.” Obviously, no abuse is acceptable or excusable, and no one questions that. But these are still extreme cases, which fortunately are a minority. Most of the time, therapists are simply subject to the same human flaws that affect us all. Sometimes, meeting a practitioner who is not “perfect” allows us to become aware of our own shortcomings, or even to understand who we don’t want to be. This has happened to me many times, and the lesson was at least as valuable, if not more so. Fear and the need for control are not necessarily good counselors.

And to complicate things further, some people experienced spectacular healings with shamans with a shady reputation, and others were disappointed by impeccable curanderos. We need to remember that the shaman is not the only determining factor, far from it. The most important part is the patient himself, and his ability to use these tools to walk towards his own healing.

We have to admit it: with these medicines, it is almost impossible to know what we are going to experience. It is sometimes necessary to take the leap of faith, and simply to trust in life, plants and people. Perhaps, instead of wanting at all costs to avoid an experience whose purpose we do not really know, it will always be preferable to go there in responsibility – and with the will to make it a constructive teaching, whatever it may be?

Photos credits:

sacredvalleytribe.com

sasint / pixabay

kellepics / pixabay

0